Mt. Hood forecast at the summit ±

100mph wind gusts, two feet of snow in 12 hours - o what fun!

Here is today's big-storm solution, similar to yesterday but low pressure not as low. And I'm hearing thunder as I type!

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Basic Stuff about Weather Models

So I clicked on the summit of Mt. Hood to get this forecast - elevation 11200 and change.

Here's the forecast - well kinda? Forecast is at 9623' as shown at the bottom.

What's really happening at the summit?!?

Ah the simple joys of creating models to predict chaos.

The complex world has to undergo some 'simplifying assumptions' for models to have any chance of simulating the weather in a timely manner. Step one is to break down the region to be forecast into a set of regular chunks: a grid. You could choose a myriad of methods to make a grid - clearly this image shows thar a large set of squares is doing the job. Each square is crammed with average data for that little bit of Earth. If you look at Oregon's high point in the real world you notice that just north of the summit it drops to 7000' in a hurry, courtesy of Coe and Eliot glaciers and their centuries of heavy grinding - hence this square includes both the summit and a steep plunge. Models can use hexagons or other grid shapes, but squares are nice in a few ways. For one they are made up of more squares, also you can make a square out of several of these squares. Either way it's still a square, and a model that runs squares can be calibrated run with different squares. Handy!

So why not make smaller squares then? Cut this square into its own 4x4 grid with more precise averages for each square, and re-run? Great idea in theory, but those theoretical weather forecasts will come out about eight hours after the storm has passed. These models are complicated, covering huge differences in conditions horizontally and vertically .. and it's changing over time, very rapidly at times and less so at other times. Superdupercomputers are now being delivered to the Weather Service for more complex modeling, but even so a grid-point that sits at 11200 and change won't appear soon.

Consider this still image of a fine set of thuunderstorms (taken in NE Portland, November 2009). At the top those clouds are congealing chunks of frozen water, which will get heavy and fall. The rain and hail at the cloud's base is clearly falling, and doing so with gusto! All this is in the still photo - now make a movie and see the cloud drift in one direction while it gets taller, more energy moves both up and down inside of it, and clear skies evaporate the new-fallen rain to make more vapor. Now make a model - GO!

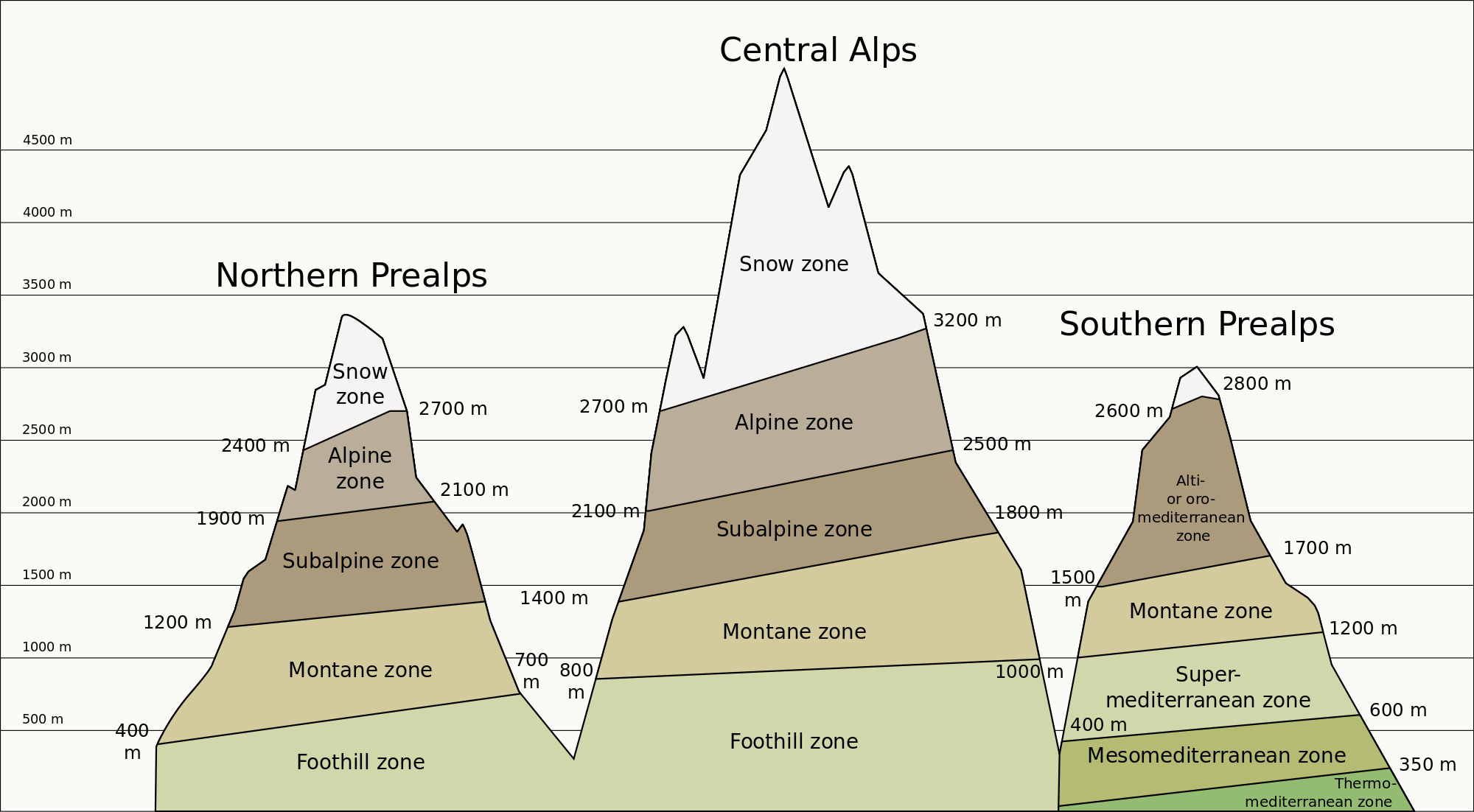

Remember how mountains can focus several climate zones? I think it was in high school I learned this stuff, back when Coe and Eliot glaciers were killing off the mastodons (kidding, I think). Climbing a mountain is like traveling toward the poles, as you get to cooler regions and the trees shrink then disappear. What mountains do over millennia a thunder-cloud can do in three hours! A dry desert heat and a moist sky can produce a cloud that is well below freezing on top (which is often higher than Mt.Everest!). Unlike mountains though, the ice zone can land in the desert for an hour, the cloud moves off, and the ephemeral mountains rebuild off the hot desert again.

No comments:

Post a Comment